Oh, Johnny Rotten, I can’t stay mad at you…

Oh, Johnny Rotten, I can’t stay mad at you…

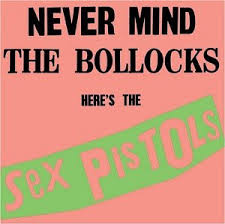

Whatever few punk fans who haven’t given up on this blog might recall that the album which really set me off on my first and most bitter vitriolic rant on punk-associated genres was Metal Box by Public Image Ltd., the group John Lydon (aka Rotten) founded after the dissolution of the Sex Pistols. I was incensed by the ugliness of the music, by its offering up of talentlessness as a virtue. That all the songs were in the neighborhood of eight minutes long didn’t help, nor did the aura of artiness about it–the implicit sense that to dislike that music was to brand oneself as churlishly quotidian in one’s musical tastes.

This album has the same lead singer, and is also characterized by a kind of ugliness and non-overabundance of musical talent, and yet I sort of love it. Or, if that overstates the case, I once loved it, and still appreciate it, even if not to actually listen to all that often. It’s not without its own degree of pretense: the group was more or less assembled by their manager, and Rotten was chosen as the lead singer based on his appearance and persona rather than vocal ability. But it doesn’t have the overweening pretentiousness of Lydon’s later efforts with PiL. The songs are sharp, focused little explosions of rage and noise and confrontation. And even if that rage was somewhat theatrical in its expression, it was nonetheless rooted in a real sense of political urgency flecked with an essential core of hopelessness. The music critic Ellen Willis, whose writings have been shaping my thinking about this stuff a lot of late, credits the UK punks with bringing a “shit-smearing belligerence”—a phrase too great not to repeat–to the punk movement that was lacking in their US counterparts.

None of which really has much to do with me or my presiding interests, whether musical or political. I don’t expect that liking this album–the most obvious choice of a punk album there is–will do much to earn me back any credentials among those punk fans I have alienated with my general antipathy to the genre. It’s just that I found my way to this album at the perfect time–the narrow sliver of my early adolescence when rage and noise were qualities I actually enjoyed in music. And the allegiance I felt toward it, even if short lived and half-assed, is not something I can slough off so easily. I loved this record once, and the echo of that feeling is not something that has entirely disappeared in the intervening years.

Which is not to say that I loved having to listen to the whole thing this time around, or that I am apt to do so again any time soon. I’ll undermine my punk rock credentials even further by admitting that it’s really only the small handful of the most obvious tracks on here– “Holiday in the Sun,” “Anarchy in the UK,” and “God Save the Queen”–that still stir any kind of pleasure in me. Those seem to me the tracks that best represent the group’s limited agenda, and the rest seem mostly like lesser versions of the same idea. (Although “Bodies,” while less musically satisfying to my ear, probably wins for shock value, and the specter of Johnny Rotten snarling the word “abortion” over and over again probably stuck with me more this time than anything else on the record.)

My lingering interest, such as it is, in those few songs, proceeds along two lines (aided, I’d imagine, by a good helping of nostalgia.) The first is that I actually like a lot of what guitarist Steve Jones does. He’s far from the most nimble or expressive guitarist there is, but there is an undeniable kind of satisfaction in his robust, loud ringing chord progressions. Compared to a lot of what is probably regarded as more authentic or far reaching punk rock, there are traces of actual musicality in what Jones is doing. It seems to me that his playing exists as much in a lineage that connects Keith Richards to Kurt Cobain–that knack for big, infectious riffs–as it does in more rarified, nihilistically satisfaction-averse punk rock circles.

The other piece that endures, of course, is Johnny Rotten himself. It’s not his rage alone that excites me, it must be conceded, but the theatricality of it. The Clash, for example, sang with much more earnestness and integrity about similar wholesale dissatisfactions with the conditions of existence, and yet I’ve never managed to legitimately enjoy their music. My enjoyment (in limited doses) of what Johnny Rotten does is ultimately more aesthetic than political. I realize that the anger he expressed was not entirely fictitious, and that the conditions he railed against were very real, but my own engagement with it, frankly, has more to do with entertainment. And if it sounds decadent or belittling of me to say so, I think its also not entirely inconsistent with his artistic intentions. I think despite himself he actually had some kernel of musical sensibility–the sneer in his voice has some real power to it, and occasionally even finds itself expressing a musical phrase quite–musically. But first and foremost, he was a performer–a performance artist. I think he’s one of the great self-created characters, right up there with Pee Wee Herman and Mr. T.

When The Sex Pistols were inducted into the hall of fame, Lydon refused to attend, sending a letter that called the place a “piss stain.” Jann Wenner read to the letter at the ceremony, and everyone had a good little chuckle, like “Oh, that Johnny..” It would have been much more unexpected–shocking, even–for him to show up in a tux and make a gracious little speech. But he was giving them what they wanted–the enduring idea of Johnny Rotten as a miscreant and colorfully sneering critic of whatever establishment he is confronted with. He was still playing his role.

Someone who was invested in the kind of upheaval The Sex Pistols portended–whether specifically or generally–would no doubt find it depressing the ways in which such revolutionary fervor gets watered down into mere nostalgia over time, and may well come to resent the Johnny Rottens of the world, the charismatic figures who live long enough to become disappointing. I have no such investment–this album came out the year I was born, and spoke to conditions in a country I have no connection to. My interest in it was always, at bottom, a kind of vehicle for a more selfish kind of teenage catharsis. And while I have no great lingering need for any such catharsis now, I still admire this album’s capacity for provoking the kind of excitement it does. I think this music felt legitimately dangerous in its own time. And even if that proved to be more a matter of theater than reality, that shock of frightening abandon still exists in the music, and still has the capacity to titillate, even if its potential to change the world has come and gone. And I think to some degree it did change the world, for better or for worse–just more musically than politically.

Source: LP – It looks like maybe an original US pressing.