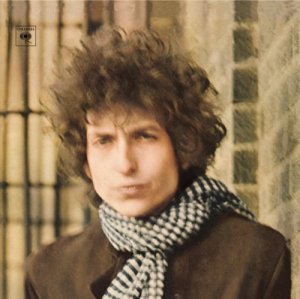

#9 – Bob Dylan – Blonde on Blonde (1966)

April 15, 2015

The opening track of an album is among the most important structural decisions an artist or producer can make in putting an album together. You need something that sets a tone for the album, usually but not always something upbeat, maybe not the very best track you’ve got, but certainly one of the best–something that will reach out and grab the listener. Debates erupt over the best opening tracks of all time (or at least they did in High Fidelity). One very solid candidate for the greatest opening track of all time, for example, would have to be “Like a Rolling Stone” from Highway 61 Revisited, Bob Dylan’s album just prior to this one–a masterpiece of a song to kick off a masterpiece of an album.

The opening track of an album is among the most important structural decisions an artist or producer can make in putting an album together. You need something that sets a tone for the album, usually but not always something upbeat, maybe not the very best track you’ve got, but certainly one of the best–something that will reach out and grab the listener. Debates erupt over the best opening tracks of all time (or at least they did in High Fidelity). One very solid candidate for the greatest opening track of all time, for example, would have to be “Like a Rolling Stone” from Highway 61 Revisited, Bob Dylan’s album just prior to this one–a masterpiece of a song to kick off a masterpiece of an album.

And then you’ve got this album, which is unbelievably great, also very much a masterpiece, except that it starts with…a piece of garbage. “Rainy Day Women #s 12 and 35,” colloquially known as “Everybody Must Get Stoned” is a perplexingly slight, annoyingly unfunny, non-endearing little nothing of a song. It doesn’t belong anywhere near an album of this calibre. And yet there it is, for all time, puzzling the music loving world by leading this tremendous album off. And it was a single! I have no idea what that’s about. And I should say that I’m no staunch opponent of baudy, intoxicated silliness, provided it’s good at what it does. “Please Mrs. Henry,” for example, from The Basement Tapes is a tremendously fun, endlessly amusing song. I could listen to that one all day. But this one is not, and never was to me, no matter the age or state of mind. Was it funny in its own time? Was it all that endlessly titillating to say “stoned” over and over? What’s the appeal? It’s hard to figure. Even Simon & Garfunkel managed to satirize it–though maybe that was meant as an homage. Either way, it’s embarrassing.

Otherwise I have very few complaints about this record. Although, since I’ve found myself of necessity leading with the negative, I will also take this moment to confess that I have never really loved the side length closing track “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” nearly as much as I feel I am supposed to. I have no qualm with the basic long and wordy format Dylan indulged in from time to time, provided it manages to hold my interest. Indeed, some of his very finest songs, like “Desolation Row” and “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” fall into that category. Those I can listen to frequently and without fatigue. But this one, whether for its rather lugubrious pacing, or its relative lack of captivating images, or both, always feels like a bit of a snoozer to me.

I realize that mine is not a popular opinion. Many people seem downright reverent about this one, and regard it as among Dylan’s true masterpieces. My theory is that he was so smart and wise-assed and evasive that people are suckers for those rare times he offers up some glimpse of tender, heartfelt emotion, and tend to overestimate the songs in which he does so. Vast swatches of Blood on the Tracks fall into that category, as does “Sara,” another long, lugubrious song which specifically references this one. Even Dylan himself proudly announced that this was the best song he’d ever written shortly after he recorded it. But he was young and in love–with the subject of the song, and with his own seemingly bottomless capacity for generating smart, surrealistic verses–and perhaps was inclined to overestimated his latest creation. I doubt he’d say the same thing now.

Many critics have observed that it seems in some indistinct way to echo “Visions of Johanna” back toward the beginning of that album, and I think I kind of sensed that on this listening as well. Or at least I held “Visions of Johanna” up as a song that accomplishes much more with much greater economy. With no disrespect intended toward “Pledging My Time,” the fine little blues that precedes it, it is the album’s first emphatically great song, and one of Dylan’s most enduring masterpieces. It swaps out the compelling strangeness of “Desolation Row” type material for something equally brilliant but more mature feeling. In lines after line of tremendous intelligence and sensitivity, it manages to create a scene that feels as much like a short story as it does a poem, albeit one without all that much in the way of a narrative thrust. It’s a lovely, slightly occluded view of a small, intimate cast of characters and the brooding, self-conscious reflections of its narrator, and it sounds absolutely beautiful. A perfect song is rare, and a perfect song clocking in at over seven minutes almost unheard of, but to me, this one really qualifies for that distinction.

It’s possible that it’s the best song on the album, although it has a lot of competition. Through an impressive array of musical styles and emotional tenors, song after song operates at a stunningly high level. Hard, stinging Chicago blues sits comfortably next to lilting acoustic folk tunes, interspersed with things that sound about as close to real pop songs as Dylan ever wrote. Overall, it’s certainly a candidate for his most musically satisfying album, and it is the one he famously described as coming closest to the sound he had in his head–“that thin, that wild mercury sound.” The mood shifts around similarly, though with style not necessarily predicting tone. One of the harder blues tunes, for example, “Leopard Skin Pillbox Hat,” is also one of the most jubilantly surreal and hilarious. Here and elsewhere, one hears his voice verging in the direction of the standard stupid Dylan impersonation, but what those unimaginative imitators miss is how much fun he’s having–how in he is on the joke: “I saw you making loooove with him–you forgot to cloooose the garaaaage doooooor!” Though the album moves through as many emotional tones as it does musical ones, if there is a presiding spirit to the album, it is Dylan’s irrepressible joy in his own remarkable powers. He is a genius at play, and it’s downright uplifting to hear.

Some core of the “big songs” on this record I long ago concluded I had grown tired of. And maybe I had–I did listen to this record an awful lot in my teens. But I hadn’t really listened to them in a long time, and I was pleasantly surprised by how much I enjoyed songs like “I Want You” and “Just Like a Woman.” If the titular choruses of those songs still feel a bit shopworn to me, the rest of the songs were a delight to hear again. It’s not just the brilliance of the lyrics, but the elegance–the real musicality–of how it the lines flow together, almost prefiguring an Eminem degree of verbal dexterity. Other songs I had not bothered to listen to for awhile, such as “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)” and “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again” were similarly revealing to hear again, though in those cases perhaps more for their musical power than their verbal brilliance. The latter in particular has a handful of lines that feel like clunky overextensions of Dylan’s penchant for clever nonsense–“she just smoked my eyelids and punched my cigarette”–but which are redeemed by the great, driving rock feel of the song, carried especially by the excellent session drummer. “One of Us Must Know” is pretty great too, in a more brooding, sinister way, and is noteworthy for being the only track to feature a plurality of Hawks (or future members of The Band), whereas Robbie Robertson is the only one whose playing appears throughout the album.

A lot of the songs that I never did tire of–ones that I have listened to with pleasure all these many years–are from the back half of the album, the region where a double album might usually be expected to start losing focus. “Absolutely Sweet Marie” and “Obviously Five Believers” in particular are perfect, tight little rockers, tracks who comparatively minor stature are thoroughly redeemed by being some of the most convincingly kick ass rock ‘n roll on the album. “Absolutely Sweet Marie,” in addition to containing one of Dylan’s most quoted aphorisms–“to live outside the law you must be honest”–also contains one of the more fantastically preposterous lines on the album, in which Bob Dylan sings “Anybody can be just like me, obviously.” Right…

A few of the prettier, folkier songs later on the album are also enduringly great. “Temporary Like Achilles” is especially fine–one of the most quietly fervent vocal performances on the album to the tune of a of drowsy, low-key barrelhouse blues, and a fine melody that sort of connects the line drawn between “Visions of Johanna” and “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.” “4th Time Around” is an interesting one–if perhaps a bit more conceptually than in practice. It’s an answer song to The Beatles’ “Norwegian Wood,” which in turn was among the most explicitly Dylanesque of their efforts. Ultimately, I don’t think it’s quite as good a song as that one–or at least not as memorable melodically. The lyrics are better, because Dylan was a better lyricist than John Lennon, but don’t stand out as much as a highlight in the context of his own work–especially on an album this great. I have always loved the gum thing, though–in the course of the song’s narrative, he offers his lover a stick of gum early in the song. Several verses later, they’re arguing and he tells her “you’re words aren’t clear–you better spit out your gum.” It’s like a small, perfect little comedic vignette in the midst of an otherwise slightly precious story song, and reminds me of Chekhov’s axiom about a gun appearing in the first act. It’s like an unusual little show of above and beyond craft on an already extraordinarily well constructed collection of songs.

Of Dylan’s three mid sixties masterpieces, of which this is the last and most ambitious, this was also the last to come my way. Bringing it All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited seemed to come into my life almost simultaneously (or at least I can’t remember which one my father gave me first). The two of them opened my ears to Dylan’s genius, and in some sense ushered in my adult taste in music (even if I was just thirteen or so). It probably wasn’t that much later that I got this one, and I surely listened to it just about as intensively, and yet it has never had that same symbolic gravity in my musical life. Prior to this listening, I would have unreservedly named Highway 61 Revisited as Dylan’s best record. But right at this moment, I’m not so sure.

Those earlier records bring with them an exciting sense of discovery–the sound of one of the twentieth century’s most important artistic figures coming in to his own–simultaneously discovering and revealing what he was capable of, stretching himself out over a void of artistic improbability. And if the first of those albums is slightly tentative and uneven in its brilliance, the second is a much more bold and cohesive statement–and the forth best album of all time according to this list. But even so, there is a sense in which Dylan was still operating in uncharted territory, and for all his bravado, it surely couldn’t have been easy being met with such vicious resistance from the folk traditionalists who had once been his fan base.

But by the time this album was being made, he had been somewhat vindicated. Even if the folk zealots were still calling his “Judas,” the tremendous success of “Like a Rolling Stone” had endorsed his musical vision, and secured his status as a major cultural figure–a role he was deeply uncomfortable with, but which also must have given him a certain degree of confidence and sense of freedom as he began work on this album. And that brash, confident spirit certainly shines through in this music. It is an album of overflowing excess–the first major double album in rock ‘n roll, and one whose density of creative accomplishment makes it still among the best ever released.

Part of the enduring joy of the album is Dylan’s gregarious grandiosity–a sense of fun and absurdity and a refreshing kind of wonder at his own genius that percolates through the entire album, and which feels entirely deserved and not the least bit unseemly in its pretensions. It’s also the very last we ever saw of this Dylan, before he retreated to the woods and reemerged as an entirely different, more quietly brilliant kind of artist. And perhaps that was just as well–it feels impossible to imagine him continuing to top himself in the same vein as this and the proceeding two records. But these three albums taken as a whole clearly represent the best of the many sides of Dylan we’ve gotten to see–the archetypal, conquering hero of wildly eccentric folk rock brilliance–and this album, the last, the longest and the most self-assured, might well qualify as the best of the lot.

Source: LP – The three disc 45 RPM MFSL set. I can’t say I loved it. It sounded very clear, of course, but it didn’t draw me in with the same immediacy as the Mono Box Set reissue, and the three disc format obscured the natural double album format of the album. Also, the mix of “4th Time Around” seemed kind of screwed up, with the insistent instrumental part almost drowning out Dylan’s voice.

April 16, 2015 at 2:30 PM

I also like this one in mono.

May 7, 2015 at 10:55 PM

[…] was first getting into good music, almost thirty years ago now, twenty years ago meant Sgt. Pepper, Blonde on Blonde, Are You Experienced, Otis Blue. Now, twenty years ago is…Dookie. Much of the stuff I […]