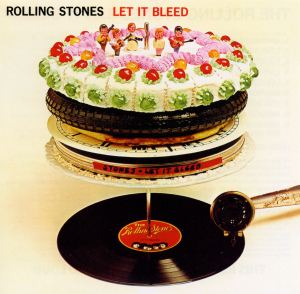

#32 – The Rolling Stones – Let it Bleed (1969)

January 21, 2015

I think of this as my favorite Stones album, and as the one of their four most acclaimed albums that I knew best coming in to this project. Listening this time corroborated the favorite part, at least so far. But I find that I really didn’t know it that well at all–at least not as well as I should. As with the rest of these albums, that patchy familiarity is an error I look forward to remedying in the years to come.

I think of this as my favorite Stones album, and as the one of their four most acclaimed albums that I knew best coming in to this project. Listening this time corroborated the favorite part, at least so far. But I find that I really didn’t know it that well at all–at least not as well as I should. As with the rest of these albums, that patchy familiarity is an error I look forward to remedying in the years to come.

If I think of it as the one I know best, it is because it’s the one my father brought home for me as a kid (it being somehow absent from his existing collection), and which he used as an explicit, not entirely successful, fulcrum point to segue me from Beatles obsession to Stones appreciation. There was, of course, the titillating similarity of title to a Beatles album (not strictly an answer record since Let it Be, though recorded earlier, came out later). I got the sense that my father appreciated the implicit undercutting (in the title and the music) of the optimistic 60s vision as espoused by The Beatles. But I was young, and hadn’t lived through that tumultuous time, and “peace and love” sounded like a better idea to me than “heart of darkness”. And I guess I still feel that way, even if not with much actual optimism to support it at this point.

Musically, the main song my father emphasized was the album’s closing track “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” which, with its big, boys choir-enhanced sound and complexity of arrangement relative to The Stones’ usual fare, felt like maybe it could be used to seduce a Beatles fan into taking The Stones a little more seriously. And it did have some of that effect. I recall liking the song a lot, and playing it a fair amount on my Dad’s stereo downstairs. But it’s noteworthy that I don’t have much memory of trying out the rest of the album, and the record (this was before the CD era hit our house) stayed firmly among my father’s library without ever migrating up into my room.

Over the years, more or less by osmosis, I began to pay more attention to the album’s opening track, “Gimme Shelter.” There’s no shortage of appreciation out there for what a spectacularly dark, malevolent masterpiece this song is, and how perfectly it captures the incipient dread seeping in all over as the dream of the 60s died away. So I won’t embarrass myself trying to come up with more words on the subject, but I’ll just add to the chorus of those citing it as The Stones best song, and an uncommonly great work of art–a genuine–and genuinely troubling–masterpiece. I hear the song pretty frequently, but hearing it from an analog source on a nice stereo this time, it sent a chill up my spine. I would maintain that The Beatles were the more consistent and the more evolutionarily significant band all told, but I think it’s reasonable to suggest that they never managed to make a track quite this powerful.

Those two songs–the opener and the closer–give the impression of being the album’s two “big” songs. That’s not to say that there aren’t a lot of great ones in between–just that it’s those tracks that have the feeling of being focused, ambitious works, indicative of a self-consciously striving for a kind of greatness that the other tracks in their looseness and laziness don’t really try to approach. Many of those in between tracks are great too–just in a more off the cuff, unpretentious, almost jam-sessiony way.

Of the songs that did feel more or less familiar to me going in, the second track, “Love in Vain,” is among my favorites. For all my grousing about white British blues, and for my lack of interest in Robert Johnson when compared to other, earlier greats of the Delta Blues, I just love the way this song sounds. It’s a Robert Johnson song (the original of which I’m not sure I’ve ever heard), preformed by a bunch of (mostly) British white guys, and yet it feels right at home to me. I love its looseness, the laconic kind of interplay of the mostly acoustic instruments, the rough hewn loveliness of the melody, and even Mick Jagger’s thick (but by no means embarrassing) performance.

Speaking of laying it on thick, the title track, which closes the first side, is yet another on the growing list of otherwise enjoyable country-tinged songs that Jaggger diminishes by his seeming inability to approach the genre without laying on a heavy, not very good parody of a southern accent. Everything else in the song suggests an all on board allegiance with the music they are playing, but Jagger’s accent just throws it all into question–and not in an interesting way. Still, it’s mostly a good one.

These two tracks also share a guest musician in Ry Cooder, who above and beyond his supportive role on these two tracks also looms somewhat large in The Stones’ legacy for having exposed Keith Richards to the open guitar tunings which would radically changed his approach to the instrument, and which were directly responsible for some of his most indelible riffs. This deserves (or at least I’ll indulge in) a bit of a sidebar here, because somewhere along the line, it came to my attention that Ry Cooder feels that he wasn’t adequately recognized for his contributions to this record, or to Keith’s development as a guitarist, and as an added quibble, feels that The Stones’ weren’t always very good about attributing their sources when borrowing a motif (or entire song) from old blues artists.

This seems kind of small minded and bitchy to me, since Ry Cooder, while a consistently excellent musician with some decent records (comprised almost entirely of other people’s music) under his belt, doesn’t really hold a candle to Keith Richards as artist. So, okay, he taught Keith some tricks on the guitar–ones that might easily have obtained from a book. But the thing is, all Ry Cooder can do is apt, respectful impressions of musicians who have come before him (or, more recently, find obscure musicians in other countries to make records with). He completely lacks Richards’ gift–genius, really–for being able to translate that kind of source material into new and interesting and kick ass music. If The Stones were a little sloppy about attributing every last little lick they borrow, I’m just about certain it wasn’t out of greed or malice, but just was part of their artistic process–one, incidentally, that mirrors the way old blues artists worked much more closely than Cooder’s indefatigable accuracy in reproducing and attributing other people’s material. Cooder is a masterful curator, and even, on records like Chicken Skin Music, an artful collagist of unlikely and disparate sources. But he’s basically never played an original note in his life as far as I can tell, where as Keith, amidst the traces of the tradition you hear in his playing, is still fundamentally and absolutely himself as an artist. So Cooder’s complaint, it seems to me, is naught but the petulant whining–the ressentiment–of the lesser man.

Anyway–the other familiar-to-me track on the first side was “Country Honk,” a loose acoustic version of “Honky Tonk Woman.” As “Love in Vain” segues into this track, I felt the thrill of familiarity and pleasure in this alternate vision of one of their bigger songs of the era. The campfire-ish informality of the track felt at first like a cool undercutting of the ever so sightly corny big polished rock feeling of the better known single. And yet as it wore on, I was compelled to concede that I sort of missed the proper version’s singular big riff, and the almost solemnly in the pocket solidity of Charlie’s Watts’s drum part. It’s fun that this other version exists (though a little weird that it appears on a proper album like this), but there’s scant ground for saying that it improves upon the more polished version.

So I guess I really did know side one pretty well, the only exception being “Live With Me,” which I’ll get to. Side two (prior to its momentous closing track) felt a good deal less familiar. I sort of knew “Midnight Rambler,” going in, though not all that well, and I feel like I still don’t. It’s one of those song that makes me feel as though I’m missing something. It’s been cited as being the quintessential Jagger-Richards songs, and one of the highlights of this album. But I pretty much just remember it as being about seven minutes of harmonica playing and Jagger rhyming “rambler” and “gambler” over and over again with a mantra-like persistence. Perhaps I’m misremembering, or haven’t ever paid it adequate attention. Maybe it’s one of those tracks that sets up an atmosphere–a dark, swaggering kind of vibe–more than it’s a reducible to being, like, a good tune. I don’t know. I’ll keep trying.

So that really only leaves three songs I had no specific sense of coming in to this listening–“Live With Me,” “You Got the Silver” and “Monkey Man.” Although my memory has already faded a few days out from this listening, I do recall being suitably impressed by each of the tracks. “Live With Me” and “Monkey Man” both felt like great, heavy rock songs–probably two of the tracks that are among the most emblematic of the gritty, tumultuous territory the band was exploring at this phase of their development. I was especially struck by “Live With Me”’s prominent, almost lead-like bass line, and was interested to discover that Keith plays the bass. This tidbit somehow drove home to me the extent to which, in their transition from one lead guitarist to another, this really is Keith’s album. It’s also among the first tracks they recorded with Mick Taylor, and is considered a landmark harbinger of the sound they would pursue over Taylor’s tenure in the group. I have fewer specific recollections of “Monkey Man,” except that it was good and heavy and dark feeling. “You Got the Silver” is a great one too, in a quieter vein. It’s the first recording Keith ever sang lead on, and I’ve always enjoyed his rare vocal contributions to the group. Mick Jagger’s insouciant, sleazy confidence as a singer and front man was historically my greatest aversion to the group, and while his talents have grown on me in recent years, I still appreciate the occasional interpolation of Keith’s less polished voice, a little more thin and unsure, but arguably therefore possessed of a bit more genuine, rough hewn soul.

There’s one Stones album left on the list–Exile on Main Street–which I’ve spent far too little time with. And while I know it is a great one, I still suspect that I’ll come away at project’s end feeling like this album is The Stones’ finest moment. It picks up from the most intriguing aesthetic developments of Beggars Banquet and gives them an album length exploration without the distracting residue of lesser experiments. At the same time, it’s a little more accessible and inviting than the increasingly, almost artily atmospheric (though still great) Sticky Fingers. It kind of hits the sweet spot between the two. For all its formal inconsistency from song to song, it is perhaps the most consistently enjoyable of their most important albums.

Source: LP. There’s so many variants out there that it’s impossible to nail down exactly whether its a first US pressing or what, but it’s certainly an early one. “Love in Vain” is attributed to W. Payne, let’s put it that way.