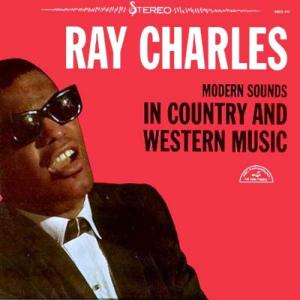

#105 – Ray Charles – Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music (1962)

May 19, 2014

When asked what kind of music I like, rather than resort to the vague (and not quite accurate) answer “all kinds,” I generally lead with soul music and country music. I like lots of other stuff too, of course, but a good percentage of my favorites fall loosely into those categories, or betray the influence of one or other, or both. Naturally, therefore, I’m especially interested in music that showcases the close relationship the two genres share–their shared roots and the sometimes blurry boundary between them.

When asked what kind of music I like, rather than resort to the vague (and not quite accurate) answer “all kinds,” I generally lead with soul music and country music. I like lots of other stuff too, of course, but a good percentage of my favorites fall loosely into those categories, or betray the influence of one or other, or both. Naturally, therefore, I’m especially interested in music that showcases the close relationship the two genres share–their shared roots and the sometimes blurry boundary between them.

The flow from one genre to the other tends to run more heavily in the direction of soul and R&B artists covering country songs. Singers like Solomon Burke, Ivory Joe Hunter and Arthur Alexander performed country songs in an R&B setting, and even wrote a few. And certain country standards like “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” and “Funny How Time Slips Away” are so frequently covered by soul artists that they have become almost standards of that genre as well. One sees less explicit influence moving back in the other direction, probably owing to a certain racial conservatism that tends to adhere to traditional country music. Gram Parsons made a point of doing countrified versions of various soul tunes to demonstrate the essential similarity of the two musical streams, although he was not in his day widely accepted as a member of the country music establishment.

Then there were many artists who managed to straddle the line, while not really belonging to either camp. In particular, a lot of white southern artists of the late 60s and early 70s–Jim Ford, Tony Joe White, Dan Penn, Bobbie Gentry, Bobby Whitlock and others–worked in a hybrid style perhaps best lumped together under Ford’s self-applied term “Country Funky.” And then there’s Charlie Rich, who experienced the greatest success as a mainstream country performer in the early 70s, but who really embodied the mingled influences of all kinds of American Music over his long and various career better than perhaps any other individual I could name.

The muddling of the genres spilled over into more mainstream rock ‘n roll as well. Both The Beatles and The Stones betrayed clear influences from both kinds of music. The Band’s earliest and best albums are great examples too. And even Elvis, the most archetypal rock ‘n roller of all, had that essential mixture of black and white influences running throughout all of his music, but really made the country-soul connection explicit on his last great album From Elvis in Memphis, and in several lesser iterations of the theme thereafter.

This album, obviously, is a major landmark of the country-soul continuum. It isn’t wholly responsible for the idea that country and soul could comfortably coexist so much as it was of a piece with a developing trend. Solomon Burke’s country-soul classic “Just Out of Reach (of My Two Loving Arms),” for example, came out the year prior to this album, and Little Willie John’s lesser known but spectacularly dramatic take on “She Thinks I Still Care” came out at about the same time. But certainly this was the album that made the connection explicit in the broader public consciousness, and in the process, helped move both country and soul music closer to the center of popular music. So while Ray Charles can’t be given sole credit for the coming together of these musical streams, it’s fair to say that this album exerted greater influence over that development than any other one album or song.

And yet for all that, it’s always been an album I’ve had trouble warming up to. The song selection is good, and Charles’s vocal interpretations of them are beyond reproach. But it is the move to the center, specifically in the spectacularly garish arrangements, that I find hard to overcome. In recent discussions on the music of Etta James and Sam Cooke from a similar period of time, I’ve had to grapple with this same problem–the mania for string section and choral accompaniment that nearly drowns these artists out in an effort to appeal to the more mainstream, white, adult audience of the day. And yet in those cases, I found myself largely able to get past the distracting arrangements–to understand the commercial (and broader socio-political) function that they served, and to focus on the more important contributions of the artist at the center.

I have had a harder time doing that with this record, as I have with many of the records Charles made after leaving Atlantic Records for the more lucrative pastures of ABC. Certainly he made many fine recordings at ABC, among them great straight ahead soul tracks like “Hit the Road Jack” and “Unchain My Heart” that rival some of his Atlantic sides. And yet I tend to associate this period of his work primarily with these heavily orchestrated, stylistically diverse kind of albums whose intent I can appreciate, but which I am rarely moved to listen to. In the case of Sam Cooke and Etta James, it is unavoidable that some of their best work was thus marred, and thus must be endured. But in the case of Ray Charles, his Atlantic recordings are so much more viscerally satisfying that it is difficult to imagine opting to listen to records of this sort instead.

Certainly there are exceptions, both on this record and elsewhere. Few would argue, for example, that his reading of “Georgia on My Mind” is not a masterpiece, even with its somewhat sodden arrangement. On this album, the obvious standout is “You Don’t Know Me,” on which Charles’s performance is sufficiently powerful to have all but erased all memory of Eddy Arnold’s original. I’m sure there are many contemporary lovers of this song who are not even aware that it began its life as a country song, and who have no idea who Eddy Arnold was. It is simply a Ray Charles song now.

As garish as the strings and chorus on that and other tracks are, my deepest antipathies are actually reserved for some of the upbeat numbers such as “Bye Bye Love” and their shrill, piercing horn section accompaniment. At this faster clip, Charles’s ability to overcome the arrangement with a nuanced performance is curtailed, and the horn parts sound to me not so much soul or even jazz-based as they just sound like showbiz. Much of the first side passed for me in this state of vague annoyance, almost wishing someone would (or could) release a stripped down copy of this music–just Charles and a basic band, without all that exhausting sonic schmaltz around it.

Realistically, the first side is probably about as far as I have gotten in most of my previous attempts to listen to this record, because by the time I got to side two, I found myself relaxing into the music a bit more. It seemed to me that the objectionable arrangements gradually became less aggressively interwoven with the actual music, the obnoxious horn string or choral parts relegating themselves more and more to the beginnings and endings of songs, leaving the meat of the song relatively unspoiled. There’s a string of slower songs making up the bulk of the side that all sounded pretty good to me, and helped improve my overall perception of the album.

The schmalz factor came back in a big way near the end with the album’s other biggest song, “I Can’t Stop Loving You.” Here too, Charles’s rendition has almost come to feel like the canonical version. In recent years, I’ve mostly frequently heard the song as performed by Kitty Wells, and yet even so, it is Charles’s more complex phrasing that I hear when I think of the song in the abstract. Like “You Don’t Know Me,” it’s a colossally great achievement of interpretation on Charles’s part, and probably the most heart wrenching version of a very widely performed song. And yet the choral part is so unremittingly hysterical, so staggeringly out of place, that it really makes Charles’s great performance difficult to appreciate as much as it deserves to be.

It’s really a shame about this record. It is of central importance to the history of American music, bringing together two of its main streams and illustrating their shared roots. It’s also a consistently great record in terms of Ray Charles’s performances. While perhaps not as deep as his earlier work, it certainly showcases his transition to being one of the great interpreters of American song who ever lived. And yet those Montovani-style strings, The Euclid Flom Chorale background vocal parts, and above all those shrill, piercing horns just make this record way more of a bummer than it ought to be. This wasn’t the first time I listened to it, and it won’t be the last. But for what a great record it is at its core, it is way too much of a challenge to get through, and that’s too bad.

Source: LP

May 19, 2014 at 5:25 PM

I find a lot of singles and albums from 1955-1966 show far too much of the producers acquiescing to the prevailing production trends in search of a hit. Janis Martin’s early rockabilly sides are marred by godawful backup vocals that make otherwise cool songs very syrupy (and if you don’t like the Jordannaires, same with Elvis). You’ve already covered Sam Cooke. You can hear the whole California “Mamas and the Papas” vocals in the Paul Revere and the Raiders sides, Chet Atkins’ style ruled country, etc. Obviously the practice isn’t limited to that time period, but that’s generally where it annoys me the most.

February 10, 2015 at 4:18 PM

The Euclid Flom Chorale. Well played, sir, well played.

February 12, 2015 at 12:47 PM

Thanks!